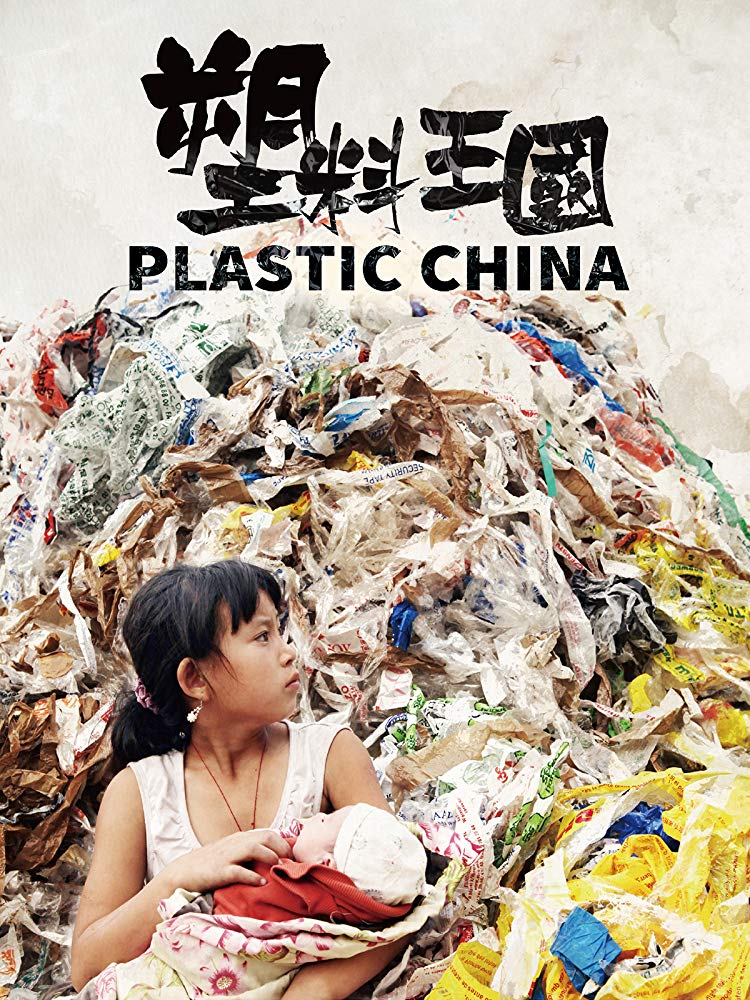

Plastic China

Newspaper articles on Prince William’s grand wedding is the magic cape for the kids; eye patches from Qantas Airways is the protection mask for the workers; a Dutch SIM card brings in a message of “Welcome to China” once inserted in a cellphone. Welcome to the land of Plastic China. As the world’s biggest plastic waste importer, China receives 10 million tons per year from most of the developed countries around the world. With high external costs impacting the local environment and health, these imports are reborn in these plastic workshops into “recycled” raw materials for the appetite of China – the world factory. This waste is then exported back to where they came from with a new face, such as manufactured clothing or toys.

Plastic China’s main character, Yi-Jie, is an unschooled 11-year-old girl whose family works and lives in a typical plastic-waste household-recycling workshop. As much as her life is poor and distorted, she’s a truly global child who learns about the outside world from the waste workshop that her family lives in and works in – also known as the “United Nations of Plastic Wastes.” She lives her happiness and sorrows amongst the waste, as well. Small packs of discarded instant black powder tells her the bitter taste of “coffee”; the English children’s learning cards teach her words like “summer” and “Father’s Day”; and broken Barbie dolls are her best friends to talk to. This is her world.

Her father promised to send Yi-Jie to school five years ago but not yet delivered on it. Instead, he spends his hard-earned money from the plastic workshop on alcohol. However, Yi-Jie keeps her wish alive of going to school one day, and we see her holding her playful campaign toward learning and schooling. Will she succeed to sit in a classroom and learn? Or will she succeed her parents as an illiterate laborer in the recycling workshop? What is her future?

Kun, the owner of this household-recycling workshop, represents money, power, and the educated class for Yi-Jie. He looks down on Yi-Jie’s family, but also depends on them to do the dirty labor that nobody else wants to do. Often, he teaches Yi-Jie to read and write, when he is in a good mood.

Kun works day and night, and ignores the physical and mental health problems of his own family and himself, just to save for a sedan car like any other factory boss in the region. He’s afraid of being looked down upon, and owning a car is the status symbol of being successful in the world.

Following these families’ daily lives, Plastic China explores how this work of recycling plastic waste with their bare hands takes a toll not only on their health, but also their own dilemma of poverty, disease, pollution, and death. All of this to eke out a daily living.

Plastic China also unveils the true face of China. The current world image of the growing China prosperity is similar to that of plastic surgery – fake and fragile, with uncertain consequences. People lose their mind over this unreal beauty, and their own fates are formed into whatever shape reality requires – just like those plastic products coming out of the mold machine.

Tracing further to the plastic waste imported from around the world, this signals and symbolizes the lives of those on the other side of the world – far away from China’s plastic-recycling workshops. When these symbolic wastes are immersed deeply in this impoverished world of these Chinese workers, we are confronted with the truth that “the world is flat,” and issues don’t go away by changing time and location. At the end of the day, as a global nation, we are all in this together, and we all play a part in this ever-changing world.